For decades, world‑class distance running looked like a blend of feel and grit. Training diaries were personal, hard to compare, and even harder to copy. What has changed is not the athlete; but our ability to dose training stress precisely. We can now apply enough physiological signal to drive adaptation without crossing the line where fatigue erodes consistency.

One of the clearest expressions of this shift is the approach associated with Norwegian distance running and popularized by athletes like Jakob Ingebrigtsen: Lactate‑Guided Threshold Interval Training (LGTIT). What appears new is largely a refinement of long-standing endurance principles, made visible through better measurement and tighter control. It is a method that uses internal load to keep “hard days” hard enough to matter, but controlled enough to repeat.

This article draws on the 2023 review by Casado, Foster, Bakken, and Tjelta on LGTIT and cross‑references it with broader endurance science and coaching practice to explain the logic behind high‑performance training design.

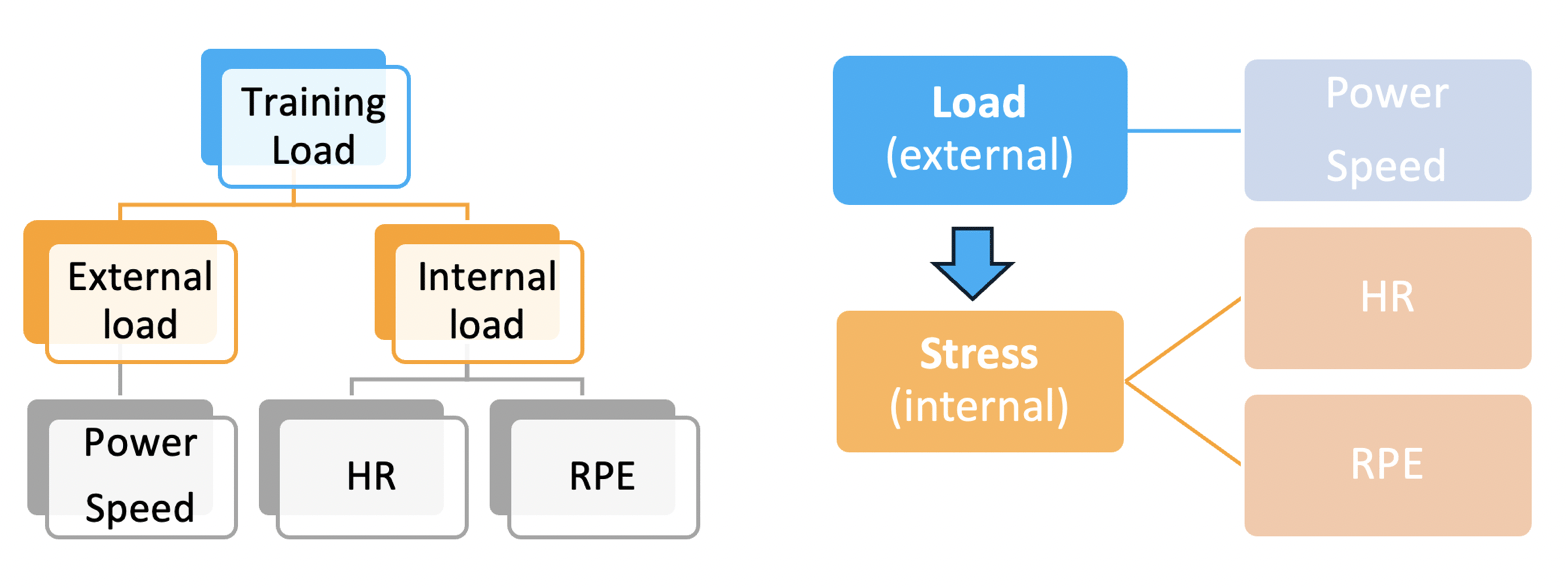

Part 1 — What the Science Says: Internal vs. External Load

Most runners manage training by external load (pace, watts, distance). That’s useful, but incomplete. The modern evolution is to prioritize internal load: how the body is responding right now; metabolically, ventilatorily, and mechanically.

Two athletes can run the same pace on the same day and accumulate very different physiological stress depending on sleep, life stress, heat, terrain, fueling, or training background.

The Two Big Cellular Signals

The review highlights the logic behind combining high-volume, low-intensity work with precisely controlled work near the second threshold. At a cellular level, this approach leverages two primary pathways:

Calcium‑Related Signaling (The Aerobic Builder): Long, easy running creates sustained muscle contractions with relatively low metabolic disturbance. This supports increased mitochondrial function, capillarization, and improved fat oxidation.

AMPK / Energy-Stress Signaling (The Efficiency Optimizer): Work near the boundary of heavy exercise; often near LT2/Critical Speed—creates a stronger energy‑stress signal. This improves carbohydrate metabolism and the "Lactate Shuttle"; your body's ability to use lactate as a fuel source.

Coach Translation: In practice, this means easy volume builds the machinery, while controlled threshold work teaches that machinery to run efficiently under load.

The Key Target - Stability: The goal is not suffering; it's a steady state where production and clearance remain in balance. This allows you to spend more "quality" minutes in a productive zone without turning the session into a recovery‑destroying race.

Part 2 — What Great Coaches Do: Controlled Intensity Beats Maximal Effort

The best training is the training you can repeat. One of the counter‑intuitive lessons in the Norwegian approach is that the best runners often "hold back" on their hard days to protect the repeatability of the training week.

Why “Volume” Really Means Repeatable Work

Recreational athletes often ask: “If I only have 5–8 hours a week, shouldn't I make every minute hard?” The answer is typically no. Volume is about repeatability, not just mileage.

Consistency over Intensity: For non-elites, "volume" means stacking months of training without injury or burnout. Hammering workouts feels productive but often leads to the pattern of big days followed by missed days.

More Truly High‑Quality Minutes: A single 20‑minute maximal tempo is brutally expensive. But breaking that into controlled intervals (e.g., 5×6 min) allows you to accumulate 30–50 minutes near the target intensity with less total stress.

Life‑Stress Management: For athletes with jobs and families, maximal efforts amplify stress hormones. Controlled intensity gives you a way to gain fitness while protecting sleep, mood, and motivation; the key determinants of long‑term progress. This isn’t “soft.” It’s strategic.

Part 3 — Bridging the Lab to Your Plan (The Proxy Guide)

Since most of us aren't taking blood samples mid‑run, we use surrogates that track the same underlying idea: staying in the right internal‑load domain.

Breathing and Speech: This is your real-time guardrail. If you can only get out clipped words and breathing feels chaotic, you’ve drifted too high. If breathing is rhythmic and you can speak short phrases, you are in the "steady hard" zone.

Critical Speed (CS) as a Proxy: CS represents the highest sustainable steady‑state intensity before fatigue accelerates non‑linearly (roughly a 30–40 minute maximal effort running). Training just below CS overlaps strongly with the intended LGTIT domain: high aerobic stress and manageable recovery.

The Treadmill as a Standardization Tool: As emphasized by Dr. Marius Bakken, the treadmill reduces "noise" (wind, terrain, surface). It allows for precise pacing and reduces impact stress, making it an ideal tool for hitting exact internal-load targets.

Rest Ratios that Prevent Drift: We use short rests (e.g., 4:1 work-to-rest) to prevent "upward drift." The aim is not to recover fully, but to ensure each rep remains in the intended metabolic domain.

RPE as the Meta-Proxy: All of these proxies ultimately converge on perceived exertion; when they disagree, RPE is often the tie-breaker. This reinforces athlete autonomy over blind metric dependence.

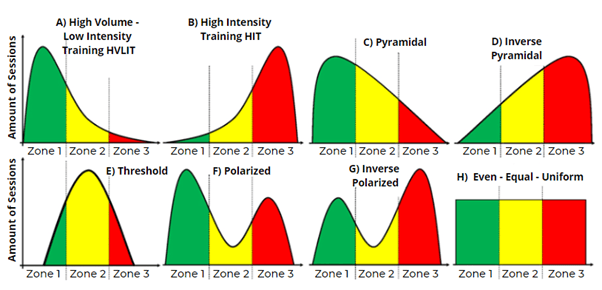

Part 4 — Polarized vs. Pyramidal: A False Dichotomy

Much confusion comes from treating Polarized (80/20) and Pyramidal systems as competing ideologies. They are actually built on the same physiological constraints. The real distinction is not distribution models, but how well intensity is controlled relative to recovery capacity.

Lactate-guided work fits both. The shared success factor is simple: Easy days are truly easy. Hard days are purposeful. And nothing is allowed to quietly become unsustainably hard.

The Synthesis: From Theory to the Training Week

How do we take these high-level scientific models—polarized, pyramidal, and lactate-guided—and distill them into a schedule you can follow?

Whether you are self-coached, working with me, or another coach, the common thread is Intensity Discipline. It doesn’t matter which "distribution model" you choose if you cannot control the physiological effort on any given day. By shifting the focus from the pace on the watch to the stability of the internal system, any runner can design a week that targets every cellular pathway without overwhelming their ability to recover.

When I design a plan for my athletes, I use this synthesis to create a "training bridge." This bridge uses high-volume principles to build your "floor" and precise threshold principles to optimize your "engine," all while protecting you from the "grey zone" of uncontrolled fatigue. On top of this I add very short neuromuscular stimuli. This approach ensures that every kilometer has a purpose, whether you're chasing an Olympic standard or a personal best.

The Anatomy of a Performance Plan

A well‑structured training plan applies one core principle: Maximize signal, minimize unnecessary stress.

Z1/Z2 Easy Days: Build the aerobic foundation and the weekly durability that allows you to handle quality work.

Threshold Intervals: Designed to drive high aerobic adaptation and efficiency while staying controlled enough to repeat.

High‑Output Strides: Short bursts that preserve neuromuscular coordination and "top-end" economy without stealing recovery from the engine.

The Goal: We aren't training you to tolerate suffering. We are teaching your physiology to solve the problem of speed more elegantly. By respecting the ceiling and building durability through volume, we raise your floor, expand your sweet spot, and turn the ceiling from a limit into a variable.

FWDMOTIONSTHLM – A page for all things swimrun, training & more.

[email protected]

fwdmotionsthlm.blog